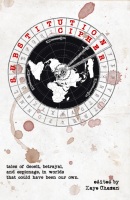

December 18! That’s when Substitution Cipher is scheduled to drop. I might have mentioned that one of my stories is in this Candlemark & Gleam collection of alternate history tales.

My first story to ever see print (e-Ink and otherwise), too.

So, I’m kind of excited.

To help focus that excitement into something useful, instead of just flailing around like Kermit up there (which is fun, mind you, but not very productive), I want to talk a little bit about the story and some of the real history that lies within. Each Tuesday, up to publication day (!), I’ll explore one of the elements in “So the Taino Call It” that I didn’t actually make up myself.

“So the Taino Call It” tells the tale of a Portuguese saboteur, Rodrigo de Escobedo (yes, he has a Spanish name–read the story to find out why!), who gets himself hired onto Christopher Columbus’s first voyage as a scrivener. His real job, though, as ordered by the King of Portugal? Scuttle Columbus’s mission and return home with knowledge of Columbus’s new sea route to Asia, if there is one.

Why would the King of Portugal want this to be done? Well, I’ll tell you. The rulers of Portugal and Castile (Spain) were the two largest competitors in the vast land grab that was the European Era of Discovery. They eventually divided the globe between themselves, thanks to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.

No, really. Two little European countries, with the help of the Pope, divvied up the Earth in 1494, and they had Columbus’s successful first voyage to thank for it, a voyage that Columbus initially tried to get Portugal to support. King John II (João) refused the offer, and so Columbus went next to the rulers of Castile, Ferdinand II and Isabella I.

Doesn’t it seem reasonable that the King of Portugal, while not interested in supporting the voyage, would want to either benefit from it himself or make sure it failed? While I didn’t find any proof of there being a real saboteur on any of Columbus’s ships, at least one that was working for another government, I did find evidence that implies that King John II wasn’t taking any chances.

According to Clements R. Markham’s translation of Columbus’s journal, on September 6, 1492, Columbus wrote that he left the Canary Islands after “having received tidings from a caravel that came from the island of Hierro that three Portuguese caravels were off that island with the object of taking him.”

I thought that was a neat moment of suspense that deserved exploration, so Rodrigo becomes the man who first sees the ships.

A flash of motion or light caught my eye as I pondered, and I looked out over the waves. There I saw ships.

I sat down, hanging my legs over the edge of the ridge, and waited as the ships sailed nearer. After an hour or more, they approached near enough that I could recognize the flag the boats flew.

Portugal.

Was this King João’s alternate plan? Why would he be sending three large warships—for so they were—close to Spanish territory if not to disrupt Colón’s voyage? My guess is that these ships will lie anchored there waiting for us to set sail. Once out at sea, they will attack and put an end to us.

I turned the caravels of Columbus’s journal into warships because I wanted beefier boats for my story to, you know, increase the drama. La Pinta and La Niña were caravels, fairly small ships that weren’t really meant for big ocean voyages. Carracks, on the other hand, were the largest European ocean-going ships of the day. The Santa Maria was a carrack. So are my warships.

Rodrigo then goes on to meet with some of the men from the ships. Intrigue ensues. Who’s Rodrigo really working for, after all? Buy the book on December 18 and find out! And join me again next week for more historic geekery.

Pingback: Pressing Matters: November 23, 2012, Edition | Candlemark & Gleam

Pingback: There’s a Little Real History in my Alternate History #4 « M. Fenn

Pingback: There’s a Little Real History in my Alternate History #5 « M. Fenn